Paging (Online Caching)

suggest changePreface

Instead of starting with a formal definition, the goal is to approach these topic via a row of examples, introducing definitions along the way. The remark section Theory will consist of all definitions, theorems and propositions to give you all informations to faster look up specific aspects.

The remark section sources consists of the basis material used for this topic and additional information for further reading. In addition you will find the full source codes for the examples there. Please pay attention that to make the source code for the examples more readable and shorter it refrains from things like error handling etc. It also passes on some specific language features which would obscure the clarity of the example like extensive use of advanced libraries etc.

Paging

The paging problem arises from the limitation of finite space. Let’s assume our cache C has k pages. Now we want to process a sequence of m page requests which must have been placed in the cache before they are processed. Of course if m<=k then we just put all elements in the cache and it will work, but usually is m>>k.

We say a request is a cache hit, when the page is already in cache, otherwise, its called a cache miss. In that case, we must bring the requested page into the cache and evict another, assuming the cache is full. The Goal is an eviction schedule that minimizes the number of evictions.

There are numerous strategies for this problem, let’s look at some:

- First in, first out (FIFO): The oldest page gets evicted

- Last in, first out (LIFO): The newest page gets evicted

- Least recently used (LRU): Evict page whose most recent access was earliest

- Least frequently used (LFU): Evict page that was least frequently requested

- Longest forward distance (LFD): Evict page in the cache that is not requested until farthest in the future.

- Flush when full (FWF): clear the cache complete as soon as a cache miss happened

There are two ways to approach this problem:

- offline: the sequence of page requests is known ahead of time

- online: the sequence of page requests is not known ahead of time

Offline Approach

For the first approach look at the topic Applications of Greedy technique. It’s third Example Offline Caching considers the first five strategies from above and gives you a good entry point for the following.

The example program was extended with the FWF strategy:

class FWF : public Strategy {

public:

FWF() : Strategy("FWF")

{

}

int apply(int requestIndex) override

{

for(int i=0; i<cacheSize; ++i)

{

if(cache[i] == request[requestIndex])

return i;

// after first empty page all others have to be empty

else if(cache[i] == emptyPage)

return i;

}

// no free pages

return 0;

}

void update(int cachePos, int requestIndex, bool cacheMiss) override

{

// no pages free -> miss -> clear cache

if(cacheMiss && cachePos == 0)

{

for(int i = 1; i < cacheSize; ++i)

cache[i] = emptyPage;

}

}

};The full sourcecode is available here. If we reuse the example from the topic, we get the following output:

Strategy: FWF

Cache initial: (a,b,c)

Request cache 0 cache 1 cache 2 cache miss

a a b c

a a b c

d d X X x

e d e X

b d e b

b d e b

a a X X x

c a c X

f a c f

d d X X x

e d e X

a d e a

f f X X x

b f b X

e f b e

c c X X x

Total cache misses: 5Even though LFD is optimal, FWF has fewer cache misses. But the main goal was to minimize the number of evictions and for FWF five misses mean 15 evictions, which makes it the poorest choice for this example.

Online Approach

Now we want to approach the online problem of paging. But first we need an understanding how to do it. Obviously an online algorithm cannot be better than the optimal offline algorithm. But how much worse it is? We need formal definitions to answer that question:

Definition 1.1: An optimization problem Π consists of a set of instances ΣΠ. For every instance σ∈ΣΠ there is a set Ζσ of solutions and a objective function fσ : Ζσ → ℜ≥0 which assigns apositive real value to every solution. We say OPT(σ) is the value of an optimal solution, A(σ) is the solution of an Algorithm A for the problem Π and wA(σ)=fσ(A(σ)) its value.

Definition 1.2: An online algorithm A for a minimization problem Π has a competetive ratio of r ≥ 1 if there is a constant τ∈ℜ with

wA(σ) = fσ(A(σ)) ≤ r ⋅ OPT(σ) + τ

for all instances σ∈ΣΠ. A is called a r-competitive online algorithm. Is even

wA(σ) ≤ r ⋅ OPT(σ)

for all instances σ∈ΣΠ then A is called a strictly r-competitive online algorithm.

So the question is how competitive is our online algorithm compared to an optimal offline algorithm. In their famous book Allan Borodin and Ran El-Yaniv used another scenario to describe the online paging situation:

There is an evil adversary who knows your algorithm and the optimal offline algorithm. In every step, he tries to request a page which is worst for you and simultaneously best for the offline algorithm. the competitive factor of your algorithm is the factor on how badly your algorithm did against the adversary’s optimal offline algorithm. If you want to try to be the adversary, you can try the Adversary Game (try to beat the paging strategies).

Marking Algorithms

Instead of analysing every algorithm separately, let’s look at a special online algorithm family for the paging problem called marking algorithms.

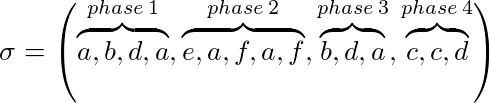

Let σ=(σ1,…,σp) an instance for our problem and k our cache size, than σ can be divided into phases:

- Phase 1 is the maximal subsequence of σ from the start till maximal k different pages are requested

- Phase i ≥ 2 is the maximal subsequence of σ from the end of pase i-1 till maximal k different pages are requested

For example with k = 3:

A marking algorithm (implicitly or explicitly) maintains whether a page is marked or not. At the beginning of each phase are all pages unmarked. Is a page requested during a phase it gets marked. An algorithm is a marking algorithm iff it never evicts a marked page from cache. That means pages which are used during a phase will not be evicted.

Proposition 1.3: LRU and FWF are marking algorithm.

Proof: At the beginning of each phase (except for the first one) FWF has a cache miss and cleared the cache. that means we have k empty pages. In every phase are maximal k different pages requested, so there will be now eviction during the phase. So FWF is a marking algorithm. Let’s assume LRU is not a marking algorithm. Then there is an instance σ where LRU a marked page x in phase i evicted. Let σt the request in phase i where x is evicted. Since x is marked there has to be a earlier request σt* for x in the same phase, so t* < t. After t* x is the caches newest page, so to got evicted at t the sequence σt*+1,…,σt has to request at least k from x different pages. That implies the phase i has requested at least k+1 different pages which is a contradictory to the phase definition. So LRU has to be a marking algorithm.

Proposition 1.4: Every marking algorithm is strictly k-competitive.

Proof: Let σ be an instance for the paging problem and l the number of phases for σ. Is l = 1 then is every marking algorithm optimal and the optimal offline algorithm cannot be better. We assume l ≥ 2. the cost of every marking algorithm, for instance, σ is bounded from above with l ⋅ k because in every phase a marking algorithm cannot evict more than k pages without evicting one marked page. Now we try to show that the optimal offline algorithm evicts at least k+l-2 pages for σ, k in the first phase and at least one for every following phase except for the last one. For proof lets define l-2 disjunct subsequences of σ. Subsequence i ∈ {1,…,l-2} starts at the second position of phase i+1 and end with the first position of phase i+2. Let x be the first page of phase i+1. At the beginning of subsequence i there is page x and at most k-1 different pages in the optimal offline algorithms cache. In subsequence i are k page request different from x, so the optimal offline algorithm has to evict at least one page for every subsequence. Since at phase 1 beginning the cache is still empty, the optimal offline algorithm causes k evictions during the first phase. That shows that

wA(σ) ≤ l⋅k ≤ (k+l-2)k ≤ OPT(σ) ⋅ k

Corollary 1.5: LRU and FWF are strictly k-competitive.

Excercise: Show that FIFO is no marking algorithm, but strictly k-competitive.

Is there no constant r for which an online algorithm A is r-competitive, we call A not competitive

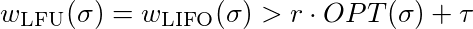

Proposition 1.6: LFU and LIFO are not competitive.

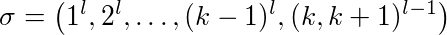

Proof: Let l ≥ 2 a constant, k ≥ 2 the cache size. The different cache pages are nubered 1,…,k+1. We look at the following sequence:

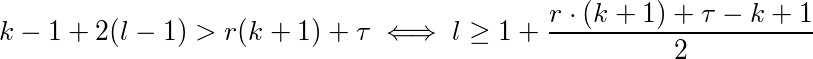

The first page 1 is requested l times than page 2 and so one. At the end, there are (l-1) alternating requests for page k and k+1. LFU and LIFO fill their cache with pages 1-k. When page k+1 is requested page k is evicted and vice versa. That means every request of subsequence (k,k+1)l-1 evicts one page. In addition, their are k-1 cache misses for the first time use of pages 1-(k-1). So LFU and LIFO evict exact k-1+2(l-1) pages. Now we must show that for every constant τ∈ℜ and every constant r ≤ 1 there exists an l so that

which is equal to

To satisfy this inequality you just have to choose l sufficient big. So LFU and LIFO are not competitive.

Proposition 1.7: There is no r-competetive deterministic online algorithm for paging with r < k.

The proof for this last proposition is rather long and based of the statement that LFD is an optimal offline algorithm. The interested reader can look it up in the book of Borodin and El-Yaniv (see sources below).

The Question is whether we could do better. For that, we have to leave the deterministic approach behind us and start to randomize our algorithm. Clearly, its much harder for the adversary to punish your algorithm if it’s randomized.

Randomized paging will be discussed in one of next examples…